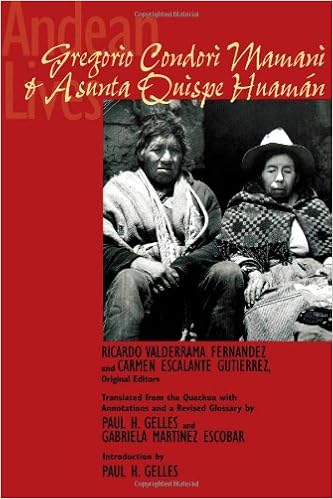

Andean Lives: Gregorio Condori Mamani and Asunta Quispe Huamán

Language: English

Pages: 213

ISBN: 0292724926

Format: PDF / Kindle (mobi) / ePub

Gregorio Condori Mamani and Asunta Quispe Huamán were runakuna, a Quechua word that means "people" and refers to the millions of indigenous inhabitants neglected, reviled, and silenced by the dominant society in Peru and other Andean countries. For Gregorio and Asunta, however, that silence was broken when Peruvian anthropologists Ricardo Valderrama Fernández and Carmen Escalante Gutiérrez recorded their life stories. The resulting Spanish-Quechua narrative, published in the mid-1970s and since translated into many languages, has become a classic introduction to the lives and struggles of the "people" of the Andes.

Andean Lives is the first English translation of this important book. Working directly from the Quechua, Paul H. Gelles and Gabriela Martínez Escobar have produced an English version that will be easily accessible to general readers and students, while retaining the poetic intensity of the original Quechua. It brings to vivid life the words of Gregorio and Asunta, giving readers fascinating and sometimes troubling glimpses of life among Cuzco's urban poor, with reflections on rural village life, factory work, haciendas, indigenous religion, and marriage and family relationships.

Introduction to Kant's Anthropology (Semiotext(e) / Foreign Agents)

Evolution and Prehistory: The Human Challenge (10th Edition)

The Drunken Monkey: Why We Drink and Abuse Alcohol

Behavioral Ecology and the Transition to Agriculture (Origins of Human Behavior and Culture)

Beyond Aesthetics: Art and the Technologies of Enchantment

to jail.” And Eusebio said: “Yes, I’ll get married.” So two months went by, and I stayed on at that house. But one night when everybody had gone to a wedding and I was watching over the house all by myself, the labor pains began. Since there were always clothes to be ironed at night, I was ironing when the pains started. At first I just told myself: “Those must be the same little aches as usual.” But it wasn’t so—they kept growing and growing until they had me sprawled out on the floor,

walking from one town to the next, offering our merchandise all the way to Sicuani. And we arrived there about a month later without any merchandise left. Then we went by train from Sicuani to Santa Rosa and to some people he knew; we bought some goods from them: powdered dyes, woven bands, and hankies. Those goods were all Bolivian—the person he knew was a smuggler. When we got all the goods together, we traveled by foot over the hills of Ayaviri with another peddler. Less than a week later,

the National Endowment of the Humanities Summer Institute “Recreating the New World Contact: Indigenous Languages and Literatures of Latin America” at the University of Texas at Austin in 1989 have proven important to this project. In particular, we would like to thank Margot Beyersdorff, Luis Morato, Dennis Tedlock, George Urioste, and especially Francis Kartunnen and Bruce Mannheim. The Anthropology Department at the University of California at Riverside is another institution that supported

the highlands in Ecuador, Peru, and Bolivia, see Babb (1989), Femenias (1991), Seligmann (1989,1993), Sikkink (1994), and Weismantel (1988). 3. she caught an ill wind and couldn’t walk: “Ill wind” is our translation of mal viento (Sp.); Asunta, in her account, calls this illness simply “wind” (viento). It should be understood that this does not refer to a “chill,” but rather to an “evil breeze,” that is, a kind of sickness that moves through the air itself and that is generated by malignant

labor, exchange labor, peonage. The term mink’a designates different kinds of labor arrangements from one region to another. Sometimes it denotes a form of peonage; other times, a replacement worker for an ayni debt; and other times, the collective and festive labor used in activities such as roofing a house, working a field, and so on. Andean peoples pool their labor in different ways, and mink’a is a generic name for several of these. See also ayni and Chapter 4, note 1. misti (Q.): “Mestizo,