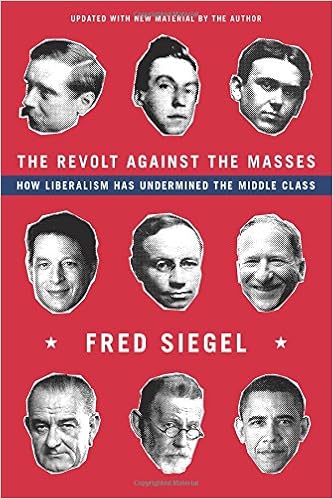

The Revolt Against the Masses: How Liberalism Has Undermined the Middle Class

Language: English

Pages: 240

ISBN: 1594037957

Format: PDF / Kindle (mobi) / ePub

The Revolt Against the Masses explores the inner life of American liberalism over the past 90 years, beginning with liberalism’s foundational writers and thinkers—such as Herbert Croly, Randolph Bourne, H.G. Wells, Sinclair Lewis, and H.L. Mencken—who despised the new worlds of mass production, mass politics, mass culture. These liberals sought to establish a true aristocracy that would serve as a counterpoint to the debasements of modern society. It was then in the seminal 1920s, that the strong strain of snobbery and contempt for the middle class, so pervasive today in the Hamptons, the New Yorker, HBO, and the Sierra Club, first defined liberalism.

Today’s brand of Barack Obama liberalism has gone further, displacing the old Main Street middle class with public sector workers, crony capitalists, and those elite arbiters of style and taste Siegel calls the liberal gentry. The Revolt Against the Masses explains how this came to be and why liberals continue to insist they act on behalf of the best interests of the middle class, even if the damned fools don’t know it.

The American Patriot's Handbook: The Writings, History, and Spirit of a Free Nation

War of the Worlds: What about Peace?

The Spectator [UK] (17 October 2015)

wrote: The progressive professional and middle class forces are framing a new culture, based on the old liberal-radical culture but designed now to hide the new anomaly by which they lead their intellectual and emotional lives. For they must believe, it seems, that imperialist arms advance proletarian revolution, that oppression by the right people brings liberty. Repression turned out to be a matter of whose ox was gored. Bernard DeVoto—who would win a Pulitzer Prize for Across the Wide

enlightened elite leadership, as Schlesinger saw it, and popular sentiment. But in the wake of Vietnam and the urban riots of the 1960s, the New Politics liberals of the post-Kennedy era saw the people themselves and the American culture they embodied as the problem that demanded government action. By 1968, the Schlesinger who had once fetishized Jacksonian workingmen and 1930s American nationalists described Americans “as the most frightening people on this planet.” Schlesinger discerned a

early 1980s, philosopher William Barrett saw it similarly: “Immured in the ’30s, we failed the decades that were to come. As the attitude of a liberal Marxism, vague enough to begin with, became even vaguer and more vaporous, it infected the whole of American Liberalism, and was to erupt again as the infantile Leftism of the 1960s.” The nuanced, empirical, and anti-Communist liberalism of the 1950s was but a brief passing phase in the long-term ideological realignment of American politics begun

term. In a replay of a liberal classic, liberals turned Bush into the faux folksy dictator of Sinclair Lewis’s 1935 It Can’t Happen Here. In 2005, New York Times columnist Paul Krugman, drawing on the caricatures associated with Sinclair Lewis, detected the creeping fascism of It Can’t Happen Here when the country-and-western group the Dixie Chicks was boycotted by former fans for songs mocking President Bush. Similarly, former New York Times columnist Anthony Lewis, a fan of H.L. Mencken, saw

him in the top one half of 1 percent of English earners. Eighteen years later, in his impassioned essay “Vindication of the French Revolution of 1848,” a polemical Mill mocked former allies and, almost alone in England, saw great promise for France ahead. Unlike both Tocqueville and Marx, who discerned elements of tragedy and farce in 1848, the solemn Mill took the rhetorical excesses of the French revolutionaries at face value. Mill had spent much of his life mocking the smug certainties of