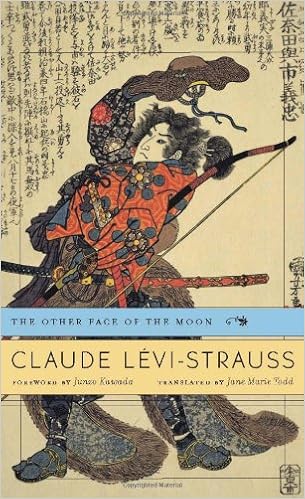

The Other Face of the Moon

Language: English

Pages: 192

ISBN: 0674072928

Format: PDF / Kindle (mobi) / ePub

Gathering for the first time all of Claude Lévi-Strauss’s writings on Japanese civilization, The Other Face of the Moon forms a sustained meditation into the French anthropologist’s dictum that to understand one’s own culture, one must regard it from the point of view of another.

Exposure to Japanese art was influential in Lévi-Strauss’s early intellectual growth, and between 1977 and 1988 he visited the country five times. The essays, lectures, and interviews of this volume, written between 1979 and 2001, are the product of these journeys. They investigate an astonishing range of subjects—among them Japan’s founding myths, Noh and Kabuki theater, the distinctiveness of the Japanese musical scale, the artisanship of Jomon pottery, and the relationship between Japanese graphic arts and cuisine. For Lévi-Strauss, Japan occupied a unique place among world cultures. Molded in the ancient past by Chinese influences, it had more recently incorporated much from Europe and the United States. But the substance of these borrowings was so carefully assimilated that Japanese culture never lost its specificity. As though viewed from the hidden side of the moon, Asia, Europe, and America all find, in Japan, images of themselves profoundly transformed.

As in Lévi-Strauss’s classic ethnography Tristes Tropiques, this new English translation presents the voice of one of France’s most public intellectuals at its most personal.

Ordinary Ethics: Anthropology, Language, and Action

Human Purpose and Transhuman Potential: A Cosmic Vision of Our Future Evolution

Encyclopedia of New Year's holidays worldwide

The Gift: Forms and Functions of Exchange in Archaic Societies

Civilizations: Culture, Ambition, and the Transformation of Nature

that it arose for me personally when I perceived it for the first time. What surprised me is my impression that it arises for the Japanese themselves. Throughout the duration of my trip I, who knew nothing about the matter, was constantly confronted with a question: “What do you think of us, what do you believe we are, are we really a people, we who in our past combined Euro-Siberian elements, others from the South Seas, who were influenced by Persia via India, then by China and Korea, who

mean the print, an art that was a revelation to me when I was six or so, and about which I have never since stopped being passionate. How many times have I been told that I was interested in vulgar things that were not true Japanese art, true Japanese painting, but were on the same level as the cartoons I could cut out from Le Figaro or L’Express! That irritation eased somewhat at times, especially in Kyoto, where, in a rather seedy Shimonsen shop, I found a triptych— oh, not very old, from the

form of poems, with their implicit quotations, facetious allusions, and hidden meanings escape us, we have only a fragmented perception of the works. In a sense, however, that is true as well for all Far Eastern painting, which is indissociable from calligraphy, and not only because calligraphy almost always occupies a place in it. Each thing repre 91 sengai sented—tree, rock, waterway, path, mountain— acquires, beyond its sensible appearance, a philosophical meaning, by virtue of

go there five times, thanks to several institutions, to which I again express my gratitude: the Japan Foundation, the Suntory Foundation, the Japan Productivity Center, the Ishizaka Foundation, and finally, the International Research Center for Japanese Studies (Nichibunken). The Japan Foundation was intent on presenting diverse aspects of the country to me over a period of six weeks. After letting me see Tokyo, Osaka, Kyoto, Nara, and Isa, the foundation had my distinguished colleagues

aesthetic aspects, the most advanced refinements of your lacquer and porcelain workers and the taste for rough materials, for rustic works—in a word, for every thing Yanagi SÇetsu called the “art of the imperfect.” It is even more striking that an innovative country, in the vanguard of scientific and technical progress, has preserved its reverence for an animist mode of thought, which, as Umehara Takeshi rightly pointed out, has its roots in an archaic past. That is less surprising when we