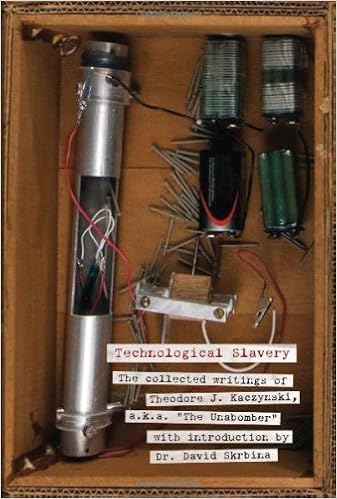

Technological Slavery: The Collected Writings of Theodore J. Kaczynski, a.k.a. "The Unabomber"

Language: English

Pages: 480

ISBN: 1932595805

Format: PDF / Kindle (mobi) / ePub

“Like many of my colleagues, I felt that I could easily have been the Unabomber's next target. He is clearly a Luddite, but simply saying this does not dismiss his argument. . . . As difficult as it is for me to acknowledge, I saw some merit in the reasoning in [Kaczynski’s writing]. I started showing friends the Kaczynski quote from Ray Kurzweil’s The Age of Spiritual Machines; I would hand them Kurzweil's book, let them read the quote, and then watch their reaction as they discovered who had written it.” — Bill Joy, founder of Sun Microsystems, in “Why the Future Doesn’t Need Us,” Wired magazine

Theodore J. Kaczynski has been convicted for illegally transporting, mailing, and using bombs, resulting in the deaths of three people. He is now serving a life sentence in the supermax prison in Florence, Colorado.

The ideas and views expressed by Kaczynski before and after his capture raise crucial issues concerning the evolution and future of our society. For the first time, the reader will have access to an uncensored personal account of his anti-technology philosophy, which goes far beyond Unabomber pop culture mythology.

Feral House does not support or justify Kaczynski's crimes, nor does the author receive royalties or compensation for this book. It is this publisher’s mission, as well as a foundation of the First Amendment, to allow the reader the ability to discern the value of any document.

David Skrbina, who wrote the introduction, teaches philosophy at the University of Michigan, Dearborn.

Relentless Strike: The Secret History of Joint Special Operations Command

Long Mile Home: Boston Under Attack, the City's Courageous Recovery, and the Epic Hunt for Justice

Cold War (Tom Clancy's Power Plays, Book 5)

Terror and Consent: The Wars for the Twenty-first Century

“About 45 percent of Australian men said they ‘often’ or ‘almost always’ felt stress.”60 “There is certainly a lot of anxiety going around. Anxiety disorder…is the most common mental illness in the U.S. In its various forms…it afflicts 19 million Americans….”61 “According to the surgeon general, almost 21 percent of children age 9 and up have a mental disorder, including depression, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and bipolar disorder.”62 “The state of college students’ mental

successful career, and when he is older and richer and has status and prestige, he comes to the conclusion that the system is not so bad after all, and that it is better to adapt himself to it. There are further reasons to believe that your plan cannot succeed. The plan requires that the movement should remain secret and unknown to the public. But that is impossible. One can be quite sure that some member of the movement will change his mind or make a mistake, so that the existence of the

mention the following: For about four years beginning on May 5, 1998, the date on which I first arrived at the prison where I am now held, I was visited almost every day by one or both of the two prison psychologists, Dr. James Watterson and Dr. Michael Morrison. Drs. Watterson and Morrison did not believe these visits were necessary, but their superiors in the Bureau of Prisons had ordered them to visit me every day. In the course of four years we got to know each other rather well, and Drs.

or later the reformers relax and corruption creeps back in. The level of political corruption in a given society tends to remain constant, or to change only slowly with the evolution of the society. Normally, a political cleanup will be permanent only if accompanied by widespread social changes; a SMALL change in the society won’t be enough.) If a small change in a long-term historical trend appears to be permanent, it is only because the change acts in the direction in which the trend is already

of the household, Coon also indicates that such foods might indeed be shared with other families if the latter were hungry.240 Notwithstanding their individualistic traits, the Cheyenne (and probably other Plains Indians) placed a high value on generosity (i.e., voluntary sharing),241 and the same was true of the Nuer.242 The Eskimos with whom Gontran de Poncins lived were so generous in sharing their belongings that Poncins described their community as “quasi-communist” and stated that “all