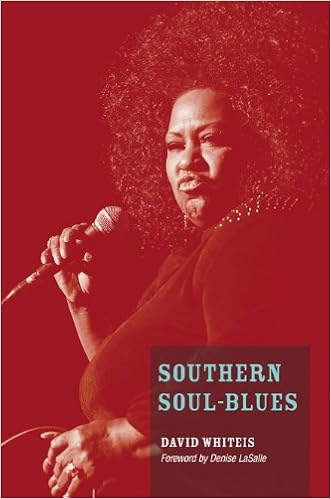

Southern Soul-Blues (Music in American Life)

Language: English

Pages: 344

ISBN: 0252079086

Format: PDF / Kindle (mobi) / ePub

DeadBase 50: Celebrating 50 Years of the Grateful Dead (Anniversary Edition)

American Ballads and Folk Songs (Dover Books on Music)

Future Days: Krautrock and the Birth of a Revolutionary New Music

it, in new ways. “His name was Joe Watson,” remembers Latimore. “His nickname was Black Magic. World-class keyboard player. He encouraged me to sing songs like Broadway songs and some jazz songs, ‘Bye, Bye Blackbird,’ ‘Fly Me to the Moon,’ ‘What Kind of Fool Am I’—he said, ‘You got good phrasing. That’ll make you better at the other things.’” Watson helped Benny develop his keyboard technique, but he cautioned him against falling into the trap of overrelying on it. “He said, ‘Technique doesn’t

some money in the jukebox, and I sang over Wilson Pickett’s ‘I’m in Love’ and a song that Otis Redding wrote called ‘Shout Bamalama,’ by a guy called Mickey Murray. Well, I blew David’s mind, and he told me to come to Stax for an audition.”11 Blackfoot remembers that when he went there a few days later, Otis Redding and Stax co-owner Jim Stewart were listening to a tape of Redding’s now-legendary “Dock of the Bay” session. Redding was preparing to go on tour, with Blackfoot’s old friends the

invoke his powers and earn his trust; he cavorted merrily—and a little ominously—through life and dream, wreaking his havoc and teaching his lessons along the way. During the long nightmare of slavery in North America and its seemingly endless aftermath, the trickster evolved into a real-world hero, a necessity for people to believe in—and become—in order to survive. In the day-today struggle for survival, he (and she) learned to don masks of subtlety and deception, sometimes “playing the fool”

of defiance than a hoochie-mama’s strut. And her bluesy alto work on “Blow That Thang Sweet Angel” was both raucous and lively. But offerings such as “Outside Tail” (“You think you can take my man by spreading your legs”) and “The Tongue Don’t Need No Viagra” sounded mostly like attempts to get easy laughs, and the stop-time, twelve-bar title song came off as a by-the-numbers attempt to cash in on the tradition of bad-mama proclamations recorded by progenitors such as Koko Taylor. Meanwhile,

a chance to experience being on the road with Marvin Sease, he started teaching me how to put songs together and how to write what I’m feeling.” Charles stayed with Sease for about five years. Sease encouraged him to get some of his newly written songs recorded; he even offered to help produce them. After laying down twelve tracks to serve as a demo CD, Charles went to Jackson, Mississippi, to audition the disc for Malaco. Malaco had developed a reputation for signing and developing artists with