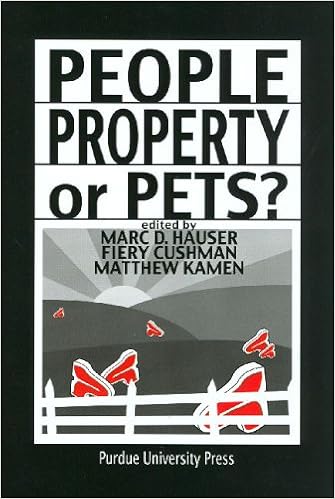

People, Property, or Pets? (New Directions in the Human-Animal Bond)

Marc D. Hauser

Language: English

Pages: 230

ISBN: 1557533806

Format: PDF / Kindle (mobi) / ePub

Blacked Out: Government Secrecy in the Information Age

The Law of Occupation (International Law in Japanese Perspective)

The Cambridge History of Law in America, Volume 2: The Long Nineteeth Century, 1789-1920

Global Governance: Why? What? Whither?

Patent Challenges for Standard-Setting in the Global Economy

rights, we must also admit that some cognitively high-functioning animals possess these rights (Dombrowski 1997). While the AMC may seem initially compelling, there are several reasons why marginal humans demand greater moral obligations from us than do nonhuman animals, and therefore why the AMC does not really justify animal rights. First, we can summarily exclude infants from the class of marginal cases because even though they do not currently have sufficient rational and moral capacities to

the right to legal standing in court, to the right not to be treated as property. Yet another step removed are the real-world consequences of abstract rights. Does the right to have one’s interests considered preclude biomedical experimentation? Can non-property be eaten? Gary Francione, one of the leading proponents of the view that animals be removed from the legal category of property, emphasizes that the law plays the role of bridging the gap between our philosophical commitments and our

locating food, may indeed approach that of mammals (Griffin 2001). Animals, therefore, are far from mindless robots. They perceive other animals and objects around them, and change their own actions based on that information. Some possess the ability of self-recognition. They use tools, build elaborate structures, and possess remarkable memories and conceptions of spatial relations. They have needs, wants, and desires. They communicate with one another, often in astounding ways, and some have

point needs to be made about what can and cannot be patented. In most cases of patented genetic modifications, patents have been issued for gene-phenotype relationships that have been experimentally created and do not naturally occur. However, the potential exists to patent a naturally occurring phenotype. If I can demonstrate through knockout experiments a definite relationship between a genotype and a phenotype, even if the phenotype is rather common, I can patent that discovery. I would then

view: We should make it quite clear that the claim to equality does not depend on intelligence, moral capacity, physical strength, or similar matters of fact. Equality is a moral idea, not an assertion of fact. There is no logically compelling reason for assuming that a factual difference in ability between two people justifies any difference in the amount of consideration we give to their needs and interests. (Singer 1975) So what counts as having an interest? A being has interests if it has