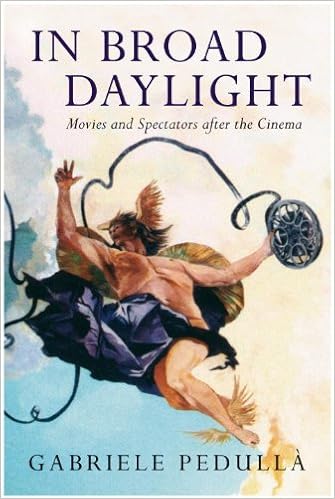

In Broad Daylight: Movies and Spectators After the Cinema

Language: English

Pages: 182

ISBN: 1844678539

Format: PDF / Kindle (mobi) / ePub

From plasma screens to smartphones, today moving images are everywhere. How have films adapted to this new environment? And how has the experience of the spectator changed because of this proliferation? In Broad Daylight investigates one of the decisive shifts in the history of Western aesthetics, exploring the metamorphosis of films in the age of individual media, when the public is increasingly free but also increasingly resistant to the emotive force of the pictures flashing around us. Moving deftly from philosophy of mind to film theory, from architectural practice to ethics, from Leon Battista Alberti to Orson Welles, Gabriele Pedullà examines the revolution that is reshaping the entire system of the arts and creativity in all its manifestations.

100 Years of European Cinema: Entertainment or Ideology?

The Cinema of Errol Morris (Wesleyan Film)

The Toho Studios Story: A History and Complete Filmography

Writing a Great Movie: Key Tools for Successful Screenwriting

human life in all its aspects, wide or narrow, is so intimately connected with architecture, that with a certain amount of observation we can usually reconstruct a bygone society from the remains of its public monuments. From relics of household stuff, we can imagine its owners “in their habit as they lived.” Honoré de Balzac, The Quest of the Absolute As to the visual elements, the stage designer has a more powerful art at his disposal than the poet. Aristotle, The Poetics Through the

imitation of novels or plays. Aniello Costagliola, an Italian playwright and journalist who took up film criticism in 1908, wrote for Cinema in 1912: “It’s an outright disaster! Long films have taken over the cinema!” Of course, such cries were not the only response, and in fact critics typically held positions of compromise, for instance observing that in principle “the feature-length film ought to be an exception for those works that are really worth developing thousands of meters of film”

opposite of the cinematic cave, with its implicit prison metaphors. So does the loss of the auditorium’s centrality mean the end of traditional attention? Many believe so. And yet, though it is impossible to deny the break between the world of the auditorium and the world of individual media, such readings give us an acute sense of déjà vu. The environment described in most of these studies is a tranquil bourgeois abode, usually occupied by a housewife who leaves the TV on so that the voices

period, though—in the golden age of the movie palace—it seemed that the Palladian and Wagnerian ideal of a space entirely consecrated to art was about to be realized, thanks to the marriage between the humanists’ project of educating the gaze and the modernist sacralization of the aesthetic experience. The television and the remote control declared the end of this utopia. In our story-saturated epoch, increasingly often we ask movies only to help us pass the time; or in any case this seems to be

(Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007). The Jean Epstein quote comes from “Magnification.” His idea regarding the increasing stimulation produced by modernity’s arts needs to be compared to Noël Carroll’s hypothesis, based on the most current neurophysiological studies, that we can consider zapping as a sort of homemade editing the spectator does to combat boredom—“Film, Attention, and Communication” (1996), in his Engaging the Moving Image (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003).