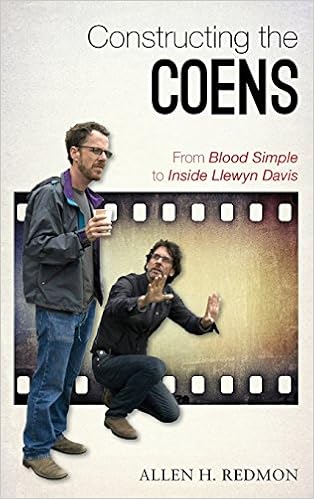

Constructing the Coens: From Blood Simple to Inside Llewyn Davis

Language: English

Pages: 192

ISBN: 1442244844

Format: PDF / Kindle (mobi) / ePub

The films of Ethan and Joel Coen have been embraced by mainstream audiences, but also have been subject to intense scrutiny by critics and cinema scholars. Movies such as Barton Fink, The Hudsucker Proxy, and Raising Arizona represent the filmmakers’ postmodern tendencies, a subject many academics have written about at length. But is it enough to reduce their features as expressions of postmodernism or are there other ways of viewing their work—not only their individual films but their entire output as a collective whole?

In Constructing the Coens: From Blood Simple to Inside Llewyn Davis, Allen H. Redmon looks beyond the postmodern sensibilities of every film written and directed by the Coens to find an unexpected range of recurring ideas expressed in and about contemporary film. In this volume, Redmon tackles all of the films in the Coen brothers’ canon by examining—among other topics—narrative coherence in The Man Who Wasn’t There, intertextuality in No Country for Old Men, and sexuality in Burn after Reading and O Brother, Where Art Thou? Additional chapters look at their films through the prisms of gender studies, adaptation studies, and a constructivist sensibility weaved throughout their work.

Considering the whole of the Coens’ output, as well as many of the topics being discussed in contemporary film studies, this book challenges viewers to reexamine their initial responses to these movies. By engaging both the familiar and foreign elements in each film, Constructing the Coens will appeal to fans of the brothers’ cinema, but also to students and scholars of film theory, adaptation studies, queer theory, and gender studies.

The Very Witching Time of Night: Dark Alleys of Classic Horror Cinema

Horror Movies - The Good, The Bad & The So Bad They're Good

The Movies of My Life: A Novel

I Hated, Hated, Hated This Movie

one” (241). Benjamin (1968) provides an interesting corrective to this concern of an absent audience in his essay “The Task of the Translator” [1923]. Here, Benjamin suggests that translations depend more on the “afterlife” of the original than any life the original might realize. The translation, Benjamin reasons, “marks [the] continued life” of the original (71). As such, the work of translation does not oblige translators to reproduce or replicate the original. Duplication is, after all, quite

of the same language can render different senses of the same words, then one has even less hope of capturing the one sense of a word in one language into the appropriate sense of that same word in another. This sort of correlation does not exist. For this reason, Borges boasts that interlingual translation has to be rejected. A broader sense of translation should be practiced, one that treats the process as “a linguistic, literary, and cultural process of transformation, as a rereading,

brothers film than one might imagine. The Coens’ sustained use of a variety of references, intertextual and otherwise, provides a sense of coherence to those who recognize them and can “keep them in [their] head.” The previous chapter addressed the impact the Coens’ insertion of unexpected narratives can have on their films. This chapter looks at the influence the Coens’ use of genre can have. Admittedly, the Coens’ dependence on genre is recognized more holistically than their willingness to

until it settles on a medium shot that looks like a silhouette. Her entire frame is in black. The pronounced light coming from the tall window in front of the character highlights Mattie’s missing arm. The final shot of the film works in virtually the same manner. The Coens cut from an extreme long shot of Mattie at Cogburn’s grave, to a long shot of her walking away from the gravesite. Mattie is dressed in black and set against a brightly lit sky. The absence of her arm is exceptionally

reverse shot reminds the Coens’ movie audience that Llewyn has an audience, but one that cannot be seen. The lights from the stage prohibit the movie audience from seeing Llewyn’s immediate audience. Another cut a few edits later places the Coens’ spectators in the midst of the Gaslight audience, but even then the shot emphasizes the distance between Llewyn and those in his room. The music cannot be heard either, and Llewyn seems exceptionally small. Performer and audience remain at a distance